Book Review: The Shadow of the Wind, by Carlos Ruiz Zafón

I am a bit late to this party, since The Shadow of the Wind by Carlos Ruiz Zafón was published in 2001 and has a strong cult following, and therefore needs no preaching to the converted. But I happened to read it only now and can't stop talking and thinking about it. At the same time, I noticed that outside of the inner circle of the anointed, my otherwise well-read and educated friends and acquaintances have never even heard of this novel. So there is a gap worth addressing here.

This book reminded me of the magic and pleasure of being completely swallowed by a story, regardless of how frayed at the edges you have become with aging. No amount of badly written, predictable, formulaic books could sedate me enough to not notice the beauty and charm, baroque language, and immersive power of this novel. Or in Ruiz Zafón's own words, this is a book for “bibliophile knights of the round table gathered to discuss the finer points of decadent poets, dead languages, and neglected, moth-ridden masterpieces”. Count me in immediately.

This is a story of Daniel Sempere, a young, sensitive boy from Barcelona, who lives a life devoted to books that he sells in a bookshop with his gentle father, while living a modest, seemingly unremarkable life surrounded by his neighbours and school friends. Daniel was “raised among books, making invisible friends in pages”, taught that books make you live more intensely. The bookshop of the Semperes is a refuge from the outer, sadistic world full of violence and upheaval that characterized Spain in the decades before, after, and during WWII. Their books were not only a source of livelihood, but created a wall that stopped and hindered the aggression and ugliness of the outside world that championed death. The novel starts with the loss, and of the most grievous kind: the loss of a mother and the sadness and tragedy of a small boy who cannot even remember her face anymore. But he gets something else in return, an obsession with a book and its writer. Seems like a poor consolation prize, however, this is a universe in which literature matters beyond anything. Daniel is introduced as the narrator at only 10 years old, and then during his subsequent teenage years, he compulsively tries to uncover the mysteries and tragedies that veil the life of one Julián Carax, and of his novel The Shadow of the Wind.

Julián Carax is an obscure author who wrote the most magical books that never sold, but transformed the lives of all who actually read them. All his readers became enchanted and in love with Julian, due to the power of his gripping storytelling. Yet he was utterly and completely failed as a writer. Go figure. Actually, don’t go figure, it makes complete sense. And who knows how many books without readers are floating unmoored out there in the gain-driven, corrupted world of book publishing? Brings to mind that Ruiz Zafón is also not as known internationally as he should have become, despite selling 20 million copies of The Shadow of the Wind alone. Critics were ambivalent when it came to him, but the word of mouth is still as complimentary as possible. Coincidence? I don’t think so.

One of the reasons why Daniel's quest resonated so powerfully within me is that one of my longstanding dreams was to become a humble reader in a publishing house, not because of career prospects of that position, or because of the pay (I understand that such jobs are most often unpaid internships), but for the weak chance that I could stumble upon a literary treasure of such a sort. An unpublishable, doomed for rejection and failure, unloved, unclassifiable manuscript that would make me dream, cherish, and champion it. Loving a book gives you purpose. Was I dreaming of becoming Nuria Monfort, the character from this novel that does exactly that, way before I even read The Shadow of the Wind? Perhaps. “We all do what we’re best at.”

The perfect audience of the novel would be someone closer to the narrator, a young adult, not a middle-aged person. Nevertheless, there is a plethora of middle-aged, older characters around Daniel, angsty, quirky, disappointed, nervous, scared and scarred, beaten by life, so that even much older readers could easily relate.

This novel is a gluttonous mixture of genres, it is a Gothic mystery, a historical testimony, a spy novel, a noir crime novel, a thriller, a Bildungsroman, a love story with pinches of magic realism. Tanta roba! I don’t mind this indecision to stick to a genre or a form. It shows the richness and vastness of knowledge and ideas, not a lack of anything.

Daniel lives in postwar Barcelona that still bears the “residue of fear”, while the subplot dedicated to the youth of Carax is the city antebellum. Duality of the setting has numerous implications. The parallelisms between the lives of Daniel and Julián strongly imply that the passage of time is an illusion and that nothing ever changes. We all compulsively repeat the same motions, mistakes, and flaws, while kicking and screaming how we live our unique lives and make our own choices. But I prefer the ante/postbellum device as a mirror that reflects the societal change. The aristocracy still mattered prewar when the invisible, yet insurmountable ramparts of the class system and family prestige reinforced the ban on transgressing the lines between the rich and the poor. Carax’s tragic flaw was looking and reaching beyond his station in life. Postwar Barcelona is the city where a community matters more, miracles of happy ends are possible, and where a poor boy can get a girl who is above him, in the end.

Ruiz Zafón was born in Barcelona, and he probably felt indebted to his home city and wished it to be the setting for his first adult novel. It was an organic backdrop, but Barcelona seems wrong for me for this story because there is nothing sunny, colorful, seasidy, or Gaudiesque in the novel’s location. Yes, the toponyms are there: the Ramblas, the Gothic quarter, the Motjuïc cemetery, even the Sagrada Familia, but it somehow does not plausibly translate into the sun-drenched, fun-loving city we all know and love. Barcelona of Daniel and Carax is rainy, gloomy, grim, and grey. The sky is always ashen or bruised, there are downpours, drizzle, and fog. The beaches are conspicuously absent, and it even snows in the end! To my mind, the setting could easily have been substituted by any other European city with a black and white, 19th-century old soul, and wears well the fate of being tragic and intrinsically cursed. I am thinking of Dresden, Prague, London, or Belgrade. I think this choice underlines that the text's atmosphere revolves around conditions within us, completely unlinked to the outside weather, climate, or place. And the story is as serious, sad, heavy, and as real as they get. Thus, it needed the Barcelona that was not frivolous. However, it is never depressing, but funny, ironic, and quick-witted, as only hyper-intelligent people manage to be. Ruiz Zafón is also openly political and makes no secret of how much he despises the army, general Franco's dictatorship, and the church. God is always mentioned “in His infinite silence”, ignoring the pleas of the suffering faithful. Amen to that.

The atmosphere is brilliantly evocative, you have a haunted city, a poignant historical period during Franco’s reign, Spanish civil war memories, and the novel brimming with eccentric figures. Ruiz Zafón is a writer with a baroque writing style, for whom simple rain is “a wreath of liquid copper”. His is a lyrical, memorable prose and there is an abundant, old-world feeling in his language and his words sound as if they depended less on the battery of a laptop than “on the strokes of the ink-pot”. His intelligent, memorable quotes effortlessly spill out from the least likely characters. He is a master of digression, Russian-doll nesting of numerous plots, and even the snippets of texts written by Carax, read as the books you would devour with joy:

“That summer it rained every day, and although many said it was God’s wrath because the villagers had opened a casino next to the church, I knew it was my fault, and mine alone, for I had learned to lie and my lips still retained the last words spoken by my mother on her deathbed…”

“What happened next?”, everything in me screamed.

Inevitably, with such a Renaissance mind and creativity, Ruiz Zafón tends to write complicated, overly long books with convoluted subplots, and unrealistically long letters that disbalance the narrative flow. All of that could be far more concise from the editorial point of view, but I wouldn’t dare remove a single word. Why would I ever wish to have less of a good thing? More is more.

Ruiz Zafón’s creativity is so boundless that there are myriads of undeveloped golden nuggets of ideas within the novel, briefly mentioned but worthy of a fully fledged book. The most compelling is the idea of the Cemetery of Forgotten Books that bears a slight resemblance to the secret library from The Name of the Rose. This is a hidden private library that harbours the books that are, for whatever reason, bound to be extinct. You enter “a spiralling basilica of shadows”, where an old manuscript, “once liberated from its prison on the shelf, sheds a cloud of golden dust”. The books are concealed and preserved there, under the shroud of secrecy, and this is a narrative knot where writers, readers, collectors, booksellers, translators, and librarians converge. If the novel had in its entirety been about this shrine dedicated to the written word, I would have greedily gulped it down. There are so many questions. What books are there, how did they arrive there, why were they forgotten, discarded, suppressed, kept out of print? Why were they unsuccessful? The Cemetery of the Forgotten Books is in Spain, after all, the country historically associated with the ghosts of the Holy Inquisition, and more contemporarily with the Catholic church, both of whom did their utmost best to silence, control, and extinguish writers and writing.

There is a neat, circular logic and structure to this novel, and we begin and end at the same point, with a father from different generations taking his son to the Cemetery of Forgotten Books, a crypt with the ideology that every book deserves to be saved. Beautiful bookending, if there ever was one.

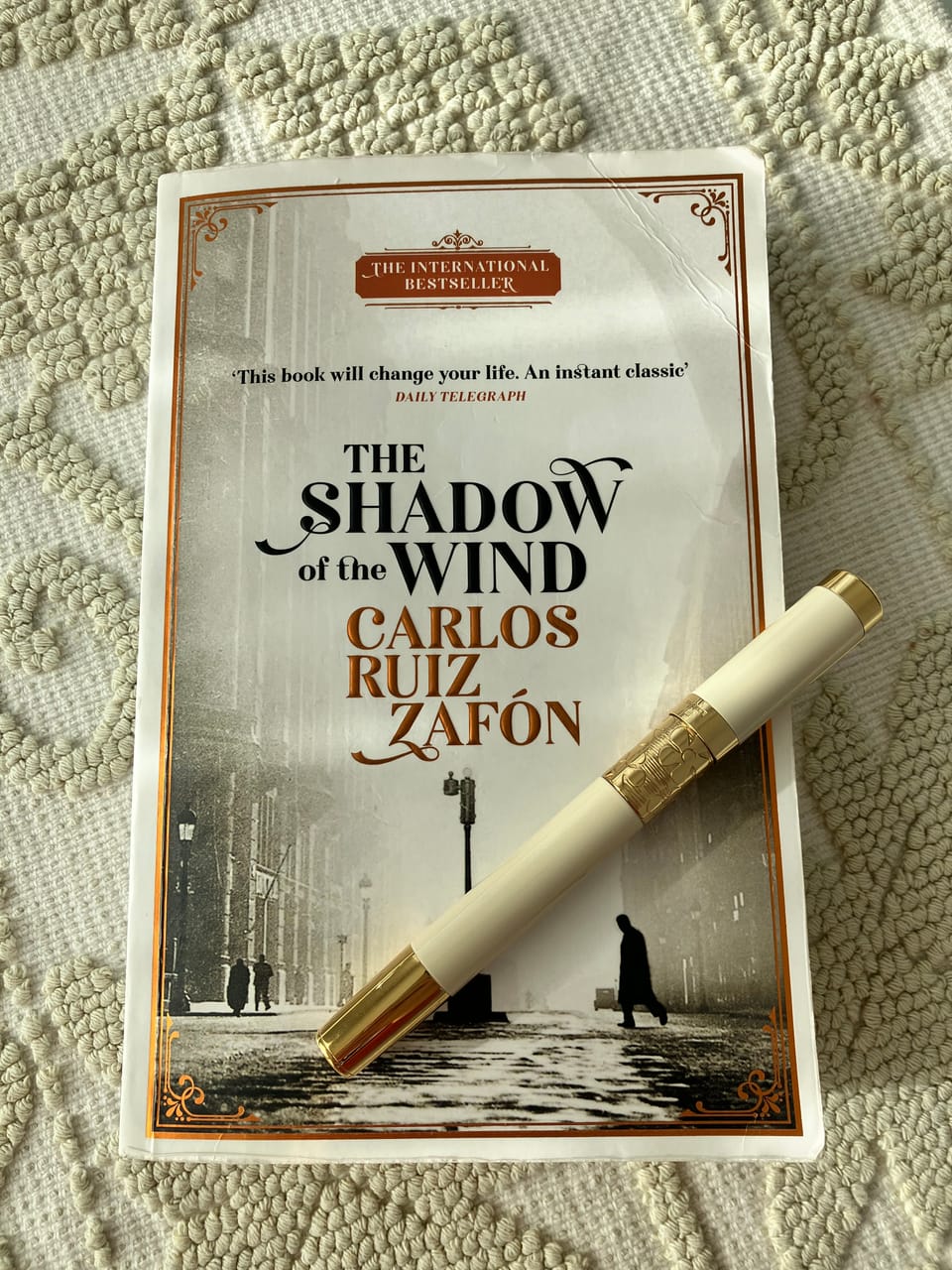

There is also a symbol in the novel that speaks so dearly to me, and that symbol is an exquisite Meisterstück fountain pen that exchanges hands, starting from, purportedly, master spellcaster Victor Hugo himself, to another bewitching, unputdownable writer Julián Carax, all the way to a writer-to-become, young narrator Daniel. This fountain pen of German craftsmanship and precision is described so expertly and bewitchingly, with a subtle, subdued hint that only if you were to possess this legendary object of wordsmithery of the highest order, you would miraculously attain that elusive gift of writing the worlds that enrapture, delight, and create entire worlds. I can't prove it, but I believe that Ruiz Zafón had this very same fountain pen.

We all crave powers, and what we crave speaks louder of us than a 500-page-long autobiography. For some, it is the fountain of youth, for others it is the sorcerer’s stone, for me and my ilk, the quest has always been about how to learn, improve, or rub onto yourself that rarest and most precious of talents: to write spellbindingly well. Did I frantically scour across Internet for a Montblanc Meisterstück pen within my budget, that would lend me an ounce of Ruiz Zafón's writerly gift? Certo. With full rational knowledge and acceptance that a pen does not make a master, I will get that fountain pen one day, just in case. I have always wanted it. Because I am a believer in magic, in the transference of powers through mysterious, irrational ways, into inheritance of luck, loss, sin, good fortune, or talent. We all are, otherwise all our special bonds in life, with that best, inimitable friend, with the only city that makes us feel at home, with that love of our life, would not make sense, if devoid of inexplicable magic that made it possible.

Carlos Ruiz Zafón died in 2020, at the age of only 55, and there can be no more new Meisterstück books from him. But to paraphrase his “There is no such thing as a dead language, only dormant minds”, there are equally no dead authors, only dormant readers. I am beyond thrilled that I woke up and got my copy of The Shadow of the Wind. There is no greater joy than to find a new-to-you writer and book to adore. The books have built me more than any other thing, experience, person, or institution in my life. I once skipped school under a false pretense that I was sick, just so that I could finish in peace The Little Women. I was that awkward and bookish ab ovo. Life gives us many identities, roles, duties, and missions, but in my heart of hearts, I will forever and ever, see myself as a reader first.